Binomial Probability and the Normal Curve

Question 1:

Find the probability of getting exactly 52 heads when flipping a fair coin 100 times.

No problem! We can solve this problem rather quickly with the assistance of our handy graphing calculator.

![]()

Question 2:

Find the probability of getting at most 52 heads when flipping a fair coin 100 times.

Yuck! Even with our handy calculator this problem can be a nightmare of calculations if we calculate and add all of the probabilities of 0 heads, 1 head, 2 heads, …, 50 heads, 51 heads, and 52 heads.

![]()

Let’s get some background information:

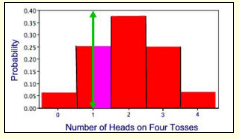

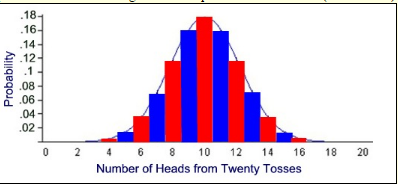

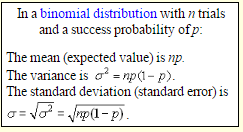

In the Binomial Probability lesson, we saw the binomial distributions for 2 flips and 4 flips of a fair coin. Statistician Abraham de Moivre (18th century) discovered that as the number of coin flips increased, the shape of the binomial distribution approached a very smooth curve. See the binomial distribution for 20 flips below, with a superimposed curve. The vertical bars represent the probabilities of obtaining each of the possible 21 outcomes (0 – 20 heads).

The super-imposed curve represents a normal distribution curve approximation for this binomial distribution. You can see that it is a good fit. The situation is such that as the number of tosses increases, the better the fit to the normal curve.

A normal distribution is really a continuous probability distribution.

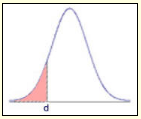

On the normal distribution curve, the probability that an outcome is greater than d equals the area under the normal curve bounded by d and positive infinity. The probability that an outcome is less than d equals the area under the normal curve bounded by d and negative infinity (as shaded in the diagram at the right).

Binomial distributions where p = 0.5 (such as this coin flipping example) are symmetric. When p is not equal to 0.5, the binomial distribution will not be symmetric. The closer p is to 0.5 and the larger the number of trials, n, the more symmetric the distribution becomes.

When the number of expected successes and failures is sufficiently large, an area under the normal curve will be a good numerical approximation of the exact binomial computation.

So how do we get the actual answer?

Binomial distributions deal with discrete variables which are made of whole units with no values between them, such as coin flips that are heads or tails, basketball tosses that make the hoop or not, or machine parts that are defective or not. Normal distributions, however, deal with continuous variables which are endless in the number of times you can divide their intervals, such as gross pay, heights, or cholesterol levels. To ensure the best approximation when dealing with these two variable types, we use a continuity correction factor.

Continuity correction:

Add or subtract 0.5 to the desired outcome to include the entire rectangle in the calculations.

In the diagram at the right, if x is a binomial random variable, n = 4, p = 0.5, and we wish to compute the probability of x < 1 using the normal curve, we will miss the pink area.

Adjustment:p ( x≤1) = p ( x≤1.5)